A widely misconceived notion seems to be that with the dawn of the digital, what is portrayed through this medium will accompany us into the future, with no expiration date. But where is the guarantee that we will be able to read the news of today on the computers of tomorrow? The 12th International Conference on Digital Preservation was held in November 2015 in North Carolina. Participants were asked why they thought digital preservation was important. The answer is not immediately obvious to the majority of people.

Attendee Alice Sara Prael, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, succinctly puts it as such “Our cultural heritage is being saved in digital formats now and it used to be that history was saved by what didn’t get thrown away and that’s not a strategy that works anymore because if we leave our digital (as it is) and hope it will live for another hundred years, it won’t.” (Coursera)

Elaine Harrington, in the UCC October 2017 colloquial, touches on this matter. Researchers are, naturally enough, focused on the research they are doing and documenting this content. However, there is a question around how we can keep this data secure moving into the future. It needs to be accessible, whether it be news sources, data, or scientific research.

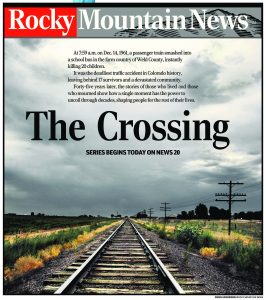

Adrienne LaFrance writes in her article Raiders of the Lost Web that “today’s great library is being destroyed even as it is being built.” She tells the story of how, in 1985, a budding journalist named Kevin Vaughan was haunted by a story he came across of a school bus collision in 1961 in Colorado, where 20 children lost their lives. In 1992, then an investigative journalist himself, he tracked down the name of the bus driver involved. In 2006, his editors at the Rocky Mountain News agreed to let him pursue the trail. The series he wrote came to be known as The Crossing.

Colorado was still suffering the ramifications of the 1999 Columbine shooting. The far reaching story of The Crossing elicited a mass wave of empathy in the region. Vaughan’s emotive narrative had significant impact on the lives of people in Colorado in their identification with the terrible loss. Vaughan assumed his piece would live forever. Its digital presence would guarantee this. Or so he thought…

In 2008, Vaughan was named a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for his work on the 34 part multimedia series. In 2009, the Rocky Mountain News went out of business, and the website followed soon after. The Crossing, and the tale it told, disappeared and fell victim to the passage of time once again.

“There’s this gradual trend toward more and more access, and of course electronic media provides the easiest and cheapest access to information that we’ve ever had on the planet…but it’s also the most easily lost. We’ve always had this tradeoff between permanence and accessibility.” ( Edward McCain, digital curator of journalism and founder of Dodging the Memory Hole at the Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute and University of Missouri Libraries.) ( “How To Preserve”)

Vaughan’s initial research had been conducted from work resurrected from dusty old boxes in forgotten warehouses. But with the collapse of the paper and resulting vanquish of the website, his own digital research and documentation disappeared without a trace.

Abbey Rumsey, writer and digital historian says, “There are now no passive means of preserving digital information. In other words if you want to save something online, you have to decide to save it. Ephemerality is built into the very architecture of the web, which was intended to be a messaging system, not a library.” (“Raiders”)

Six years after The Crossing disappeared, Vaughan re-introduced it to the Web. By serendipity alone, he had back-up. After the publishing of The Crossing, he had been asked to introduce some presentations on it, and had four DVDs made to serve this purpose. The series had been built using HTML4, and he had what he needed to rebuild the site. His son, who was studying electrical engineering and computer science at the time, took the project on, and rebuilt it according to the new standards and software now available.

Obsolescence is embedded into technology. When Sir Tim Berners-Lee formulated the web twenty years ago, he saw it as a forum for the good of mankind, where data was available for research, where all of this information could network and be democratized for the people of the world. But what we are seeing more and more of are useful ideas and research disappearing.

The problem lies in large with the fact that there is no one trusted digital vault into which content can be stored and used for future access. “Terms of service for nearly every free platform…make absolutely no promise regarding digital preservation or even the return of content to users in event of business failure or (elimination of) service.” (Elaine Harrington)

The obstacles are manifold: matters of privacy, staffing and skillsets, storage space, issues of access….The sheer volume of information we now produce is in direct competition with our capacity to preserve it and archive it for future use.

Coursera. “Why Is Digital Preservation Important?” Coursera (n.d.) Web. Nov. 2017.

Hare, Kristen. “How to Preserve Your Work Before the Internet Eats It.” Poynter, 14 Jan. 2016. Web. Nov. 2017.

Harrington, Elaine. “Preserving the Libraries of the Future.” Digital Humanities Research Colloquium, 18 Oct 2017, DH Active Learning Space, UCC. Guest Presentation.

LaFrance, Adrienne. “Raiders of the Lost Web. ” The Atlantic, 14 Oct. 2015. Web. Nov. 2017.