Category: Mapping

Crowdsourced Spatial Participation

Today’s world sees us connected as a whole in ways we could never before imagine, allowing us to contribute and participate collaboratively in an increasingly more immediate manner. Clay Shirky, in his TedTalk, “How Cognitive Surplus Will Change the World”, terms Cognitive Surplus as the free time people have on their hands to engage in these collaborative activities. There exists within these efforts a potential to create civic value. Missing Maps is a collaborative project between the Red Cross, Doctors Without Borders (MSF) and the Humanitarian OSM team. It is a project that acknowledges the abilities of the crowd and facilitates the application of the principles of crowdsourcing and open data in bridging the gap that exists between humanitarian organisations and the vulnerable in areas which are inadequately mapped. Various projects Missing Maps have initiated showcase this culture of generosity with incredible effect. James Surowiecki in ‘The Wisdom of Crowds’ elaborates on how the many are smarter than the few, and it is this collective wisdom that lies at the heart of projects such as these. (Surowiecki)

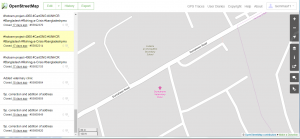

An online exploration, via Open Street Map, of the area I was raised in, Fermoy, Co. Cork, is where I chose to embark from in regards to this assignment. I set up an account, located my childhood home, which has since been converted to the local veterinary practice, and slotted this into the cartography of the area. I corrected misspellings of roads and indicated local green areas, pubs, shops and landmarks. I found this to be an interesting pursuit and a gentle introduction to mapping online.

My next step was a straightforward download of MapSwipe onto my tablet. MapSwipe serves as a worthy introduction to the Missing Maps project. It is a micro tasking platform allowing the public to support humanitarian aid in a manner as simple as basic gameplay. The task is the marking of building and roads on tiles of satellite imagery via swiping and tapping your smartphone. However, to refer to MapSwipe in such a simplistic manner serves little justice to this ingenious formulation.

MapSwipe can be installed on your mobile device. It travels with you and adapts to your lifestyle. There is no minimum participation required and every little helps.

The user brief is elementary. Scan the image for features, tap each tile when you locate the ‘bounty’, tap once for yes, twice for maybe, and three times for obscured imagery. As you swipe through maps of far flung locations, random tiles that you progress through offer words of encouragement and praise your ‘humanitarian’ efforts. There is an element of gamification tied up in the process and this extrinsic motivational technique is conducive in encouraging and maintaining the interest of participants who may have no significant ties to the countries or issues they are engaging with. The user progresses through levels and is given indicators of process. The tiles are later verified by at least three volunteers and graded by agreement so timidity on behalf of the user of fudging results should be discarded. The potential inaccurate grading of a tile is tied into the structure of the application, and this safeguard should perhaps be elaborated upon more in the guiding material for the inexperienced user.

In regards to clarity of the imagery, I observed a few minor issues. Depending on the mobile device of the user, the tiles can appear quite small and having viewed the app on both types of devices, a tablet sized device for true clarity is required. The option to enlarge tiles is farcical, regardless of device. Holding down produces a tile in the middle of the screen that is quite often pixilated in nature and is only a degree or so larger than the original option and of very little help in magnifying the image for clarity.

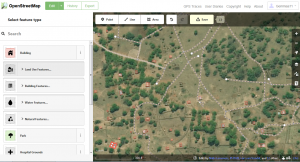

Ultimately, the accessible user interface and digital engagement of MapSwipe serves as an encouraging introduction to the more insightful and intense environs of Humanitarian OpenStreetMap whereby the user is directed to move to a desktop or laptop platform in order to engage with the tasks. HOTOSM involves an element of drawing (buildings, roads) for which a mouse is essential. I settled upon Project #3952, Malawi – Nsanje, one of the poorest areas in Malawi and one highly dependent on aid organisations. One concise tutorial and the participant is launched into the unmapped territories of various countries in need.

I found the interface of HOTOSM user friendly once I had engaged with the tutorials offered. Projects are delineated according to the skills level of the user and may be filtered along the side to suit ability levels. Each individual project also offers guidelines pertaining to the task and region in question. The task of mapping involves identifying and outlining features, tagging and classifying, and squaring or rounding off of buildings. In dense urban areas, the option exists to split that particular tile down into a more workable size. An issue that arose during my tasking, quite frequently, was that of the pink guiding grid (outside which the user should not map) disappearing when I performed the zoom function on these built up areas. In cases such as these I found myself using main roads and rivers as a point of reference so as to stay within guidelines. Once the user has uploaded their progress, the option exists to have one’s work validated. This is a comforting factor for a new user and once confidence and ability has increased sufficiently, the service of validating others’ tasks is instructive and educational in its own right.

The humanitarian aspect of the Missing Maps project, and the implications any one individual may have on a project or life, is one that I find particularly engaging, and while I remain unsure in how I may introduce aspects of crowd sourced initiatives into my work, I am resolute that I will practice mapping in my personal time. This resolution is brought about through a clear correlation between experiences and stories of friends and mapping initiatives…

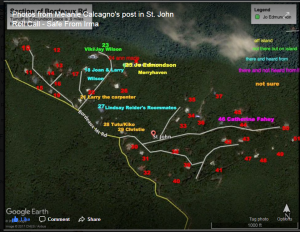

I have a personal interest in the Caribbean and the ravages of the various weather elements that its inhabitants are pitted against, particularly during hurricane system. I relocated to the small island of St. John in the United States Virgin Islands in 2003 where I saw the results of 1995’s Hurricane Marilyn still in effect in the homes and hearts of the people there. Over the six years I spent on St. John, I joined my fellow islanders each hurricane season, hunched in front of the Weather Channel, often under strict government issued curfew, anxiously watching a whirling image as it wreaked havoc on our neighbours and willing it away from our path. Hurricane season remained relatively kind to that region from Marilyn up until 2017 which saw Hurricane Irma, closely followed by Maria, truly devastating the area. This mapping assignment has proved personally evocative in opening up a window into the manner we can all help those who are vulnerable to nature’s wrath.

As the days after Irma passed, my thoughts were with friends who lived on isolated dirt roads, in adapted tree houses, atop treacherous mountains, and in the many wooden structures typical of the older style of West Indian building. Power, water, and mobile phone service was all decimated, and a serendipitous Wi-Fi hotspot proved to be a lifeline. Friends and family in the mainland and beyond sent images and maps via an emergency Facebook site manned by those familiar to the topography and people of the island. Volunteers on the ground worked with this information and daily updated, photographed and broadcast on the forum a large cardboard placard with the names of those who had been found safe and those still missing along with maps requesting specific information. A form of modern ‘coconut telegraph’ operation was borne in which the unofficial grassroots efforts of those on the ground collaborated with acquaintances further afield in rescuing and securing aid for the afflicted.

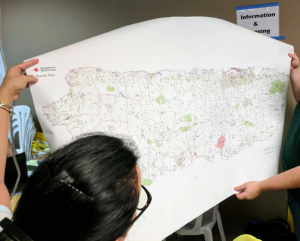

In the following days, approximately 50% of the island were evacuated to Puerto Rico, St. Croix and beyond. In a blow to fate, Hurricane Maria hit on September 16 and incurred widespread damage in areas already affected by Irma, but also decimated the islands evacuees had escaped to. My exploration of HOTOSM in this assignment informed me of the manner in which universities such as Johns Hopkins swung into action in the days following the disaster and organized mapathons where students and staff remotely mapped areas and facilitated recovery and aid efforts. Tyler Radford, HOT’s executive director, estimates that 2,800 volunteer cartographers worked in OSM in response to these hurricanes, adding over half a million buildings. The Puerto Rican relief effort is still currently underway with OSM requiring experienced users with expertise in US road mapping and Java OpenStreetMap Editor currently mapping with high detail the routes and stops of the Publico bus network that are still operating.

The manner in which technology helped facilitate a grassroots led rescue of personal acquaintances on St. John, paired with the immediacy of HOTOSM’s intervention following the devastation, serves to drive home the significance of crowdsourcing and open source mapping and the very real impact it has, and will continue to have, in peoples’ lives. The argument exists that institutions are outsourcing work via these projects but these particular instances prove to showcase how collaboration with the public elucidates information that official data recorders may not have access to, especially on smaller, more remote locations such as the Virgin Islands that are remarkable in that the community they home consists of diverse characters such as ‘snowbirds’, transient communities, and those living aboard sailing vessels. Local, personal information is key in locating such people.

Children who were born in the Virgin Islands and were evacuated as a result of the hurricanes experienced their first winter and snowflakes in 2017 as a result of the catastrophe. What was once a close community consisting of two small villages and one main road has been flung to all four corners of the earth. I believe open source and open data is the way forward in a changing world that has in many ways become smaller. The innate sense of community born in the islands is facilitated via technology daily. With increased online interaction and our ability to travel to destinations unheard of twenty years ago, more and more citizens of the world are coming to the recognition that we are all connected, and we all have influence over each other’s fates, that we are a Global Village. The success of the Missing Maps projects in these areas that I am familiar with significantly demonstrates the manner in which we may positively influence the lives of those less fortunate than us. I am certainly inspired by this assignment to maintain involvement with these initiatives both out of a humanitarian impulse and a sense of personal responsibility. Missing Maps showcases how applications such as these may be incorporated into our everyday life and affect the world and our fellow citizens for the better. The intersection of volunteers, open data and ever improving open source software, in the right hands, holds much promise.

References

“Clay Shirky: How Cognitive Surplus will change the World.” YouTube, uploaded by TEDTalks, 29 June 2010. www.ted.com/talks/clay_shirky_how_cognitive_surplus_will_change_the_world#t-131795 Accessed 09 Feb. 2018.

Day, Katie. “Surfrider Staff Scientist Provides Hurricane Relief in St. John US Virgin Islands.” Surfrider, 07 Nov. 2017. Accessed 01 Feb. 2018.

Kirk, Mimi. “The Crowdsourced Maps Guiding Puerto Rico’s Recovery.” Wired, 13 Oct. 2017. Accessed 11 Feb. 2018.

Oliver-Didier, Jose and Victor Ramirez. “OSM Puerto Rico Emerges Stronger and Ready to Help Rebuild.” hotosm, 27 Oct. 2017. Accessed 01 Feb. 2018.

Peters, Jeremy. “In the Virgin Islands, Hurricane Maria Drowned What Maria Didn’t Destroy.” New York Times, 27 Sept. 2017. Accessed 01 Feb. 2018.

Surowiecki, James. The Wisdom of Crowds. Random House, 2005.