Communication experts report that when facts do not fit a specified frame, then the public have difficulty incorporating this data into their mindset. According to Crenshaw, this leads to the stories of an untold many going unreported and disappearing through the cracks, occurrences of ‘injustice squared.” (The Urgency)

Intersectionality challenges the assumption implicit in the mainstream feminist movement that all women co-exist equally and fight the same battles. Grace Hong, a professor of Asian American and Gender Studies at UCLA, says for decades, white women didn’t have to consider any interests beyond their own because “historically, the category ‘woman’ has, implicitly, meant white women.” (Bates) Audre Lorde reports “there is no such thing as a single issue struggle because we do not lead single issue lives.”

Intersectionality may be considered a framework whereby the intersection of many types of oppression can be viewed. While Crenshaw’s immediate focus was related to race and gender “intersectionality has since been expanded to include the analysis of discrimination faced by anyone who identifies with the multiple social, biological, and cultural groups that are not favored in a patriarchal, capitalist, white supremacist society.” (Intersectional) With the onset of social media as a platform where more marginalised voices may be heard, it only makes sense that intersectionality is gaining huge ground in more recent years. The very people it encompasses are finally able to engage in the debate.

Intersectionality is built on sound principle and has undeniable merit in its foundations. However, its passage into the social media arena, and the buzzword type status it has more recently attained, means the term has at times become wrought with confusion and vulnerable to misinterpretation and misappropriation.

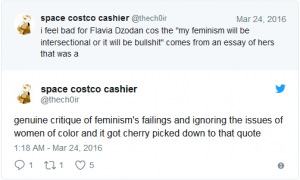

Flavia Dzodan, who identifies as a woman of color, created the infamous phrase “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit” in her essay expressing her disenfranchisement towards the feminist movement and calling for a change in the way feminism deals with issues beyond gender equality. Her call for action was embraced in a manner that stripped her original message of its context. A consumption of her message by the mainstream feminist movement saw her battle cry become a diluted catch phrase, devoid of the original meaning Dzodan had imbued it with. It was taken by the mainstream and turned into a flimsy, one dimensional version of itself, belying the strong underlying structure of her argument. As a woman of colour specifically, her slogan and rebellion were co-opted and twisted by the mainstream feminist movement to suit their agenda.

Similarly, Quartz at Work reports how the popular movement #metoo was in fact devised and set in motion by WOC Tarana Burke before being adopted and assimilated into a huge mainstream movement. While Burke is credited with having a place in the movement in Time magazine’s 2017 People of the Year, where the #MeToo movement was honoured, her name is buried deep within the article.

Moments such as these are “the result of the collective labor of women of color who turned private agonies into public battles on behalf of justice. As overdue and welcome as this reckoning feels, there’s also the unsettling reality that a movement built largely on the labor of women of color has been co-opted by a discussion that prioritizes the experiences of victims who are white, wealthy, and privileged over those who are not.” (Purtill)

“Contemporary feminist and antiracist discourses have failed to consider the intersections of racism and patriarchy.” (Crenshaw) A clash of views was witnessed at the AJC Decatur Bookfest’s keynote conversation when writers Roxane Gay and Erica Jong joined together on stage. The evening’s discourse is instrumental in highlighting how advancements must still be made in the relationship between intersectionality and feminism.

Roxane Gay (An Untamed State, Hunger) is a self-described Bad Feminist who has openly criticized mainstream feminism for its failure in acknowledging the needs of the marginalised.

Her fervent support of feminism in a different guise to that which we have traditionally associated it with and her application of the term intersectionality in her highly accessible and empathetic works has seen her star ascend greatly in popularity over the recent years. Erica Jong (Fear of Flying, How to Save Your Own Life) has long been recognized as an icon of the second wave of feminism and had a pivotal role in the sexual revolution.

The night quickly descended into an uncomfortable spectacle which saw the old school model pitted against a burgeoning new school of thought in relation to feminism and intersectionality. Jong immediately seemed out of depth and at a disconnect with her audience. She at one point requested clarity in regards to the term intersectionality, a fact which did not go unnoticed amongst the crowd. Tension emerged at Jong’s insistence that feminism has long embraced women of colour into its framework and left the two speakers at a stalemate mid-way, with Gay appearing to quietly demur. Electric Lit relay the night in a graphic comic mode eruditely here and report “the deeper they got into a discussion of racial tensions, the more the backgrounds of these two powerful writers became apparent, both their knowledge and lack thereof.”

If feminism’s goal is to uplift all women, then the inclusive nature of intersectionality should be enveloped in its fold, supporting those women whose simultaneous identities and battles are not always recognized in society. “One-size-fits-all feminism is to intersectional feminism what #alllivesmatter is to #blacklivesmatter.” (Utt and Uwujaren)

The world in which we live is filled with diversity and intersectionality is acknowledging, tackling and embracing this. One aspect of a woman’s identity cannot and should not be prioritized over another for the sake of social or political ease. The odysseyonline reports that “intersectionality is a new wave of feminism that is gaining traction with the Millennial generation.” This new wave is one that threatens to leave stalwarts in dust should their failure to recognise intersectionality’s issues and relevance in our rapidly changing world continue.

Bibliography

Bates, Karen. “Race and Feminism: Women’s March Recalls the Touchy History.” NPR, 21 Jan. 2017. Web. 5 Dec. 2017.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Scribd, Web. 4 Dec. 2017.

“Intersectional Feminism for Beginners.” Tumblr. Web. 7 Dec. 2017.

“Kimberle Crenshaw Discusses Intersectional Feminism.” YouTube. Uploaded by Lafayette College, 15 Oct. 2015. Web. 5 Dec. 2017.

MariNaomi. “Speak Up!: A Graphic Account of Roxane Gay and Erica Jong’s Uncomfortable Conversation.” Electric Literature, 10 Sept. 2015. Web. 7 Dec. 2017.

Mejias, Breann. “The Idealised Ideology of Intersectionality.” The Odyssey Online, 11 Apr. 2017. Web. 7 Dec. 2017.

Purtill, Corinne. “MeToo Hijacked Black Women’s Work on race and gender equality.” Quartz at Work, 6 Dec. 2017. Web. 7 Dec. 2017.

“Roxane Gay, Confessions of a Bad Feminist.” YouTube. Uploaded by TEDTalks. 22 June 2015. Web. 3 Dec. 2017.

“The Urgency of Intersectionality- Kimberle Crenshaw.” YouTube. Uploaded by TEDTalks, 7 Dec. 2016. Web. 7 Dec. 2017.

Utt, Jamie and Jarune Uwujaren. “Why Our Feminism Must be Intersectional.” Everyday Feminism, 11 Jan. 2015. Web. 7 Dec. 2017.

“(1982) Audre Lord, Learning from the 60s.” Blackpast, (n.d.). Web. 7 Dec. 2017

@thechOir. “I feel bad for Flavia Dzodan cos the ‘my feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit’ comes from an essay of hers that was a.” Twitter, 24 Mar. 2016. Web. 6 Dec. 2017.

@thechOir. “genuine critique of feminism’s failings and ignoring the issues of women of color and it got cherry picked down to that quote.” Twitter, 24 Mar. 2016. Web. 6 Dec. 2017.